| « 16 / 30 Mental Maps | 14 / 30 Strollology – the alienation from alienation » |

15 / 30 Fact-based Funny

“I have never laughed about a photo. But it is incredibly hard to make people cry with a comic.” (Nicolas Wild)

The silence in the studio of Nicolas Wild’s class on graphic reportages is astonishing. You hear scribbling and at time the rustling of paper. Nobody looks up when I enter the room. All the fourteen students are intensely immersed in their work. I can even hear my own footsteps. When I tell Nicolas that I am surprised by the silence, he laughs: “You need to be focused when you write and draw. You want to know exactly what you do. This is not like painting, you don’t draw with your whole body.”

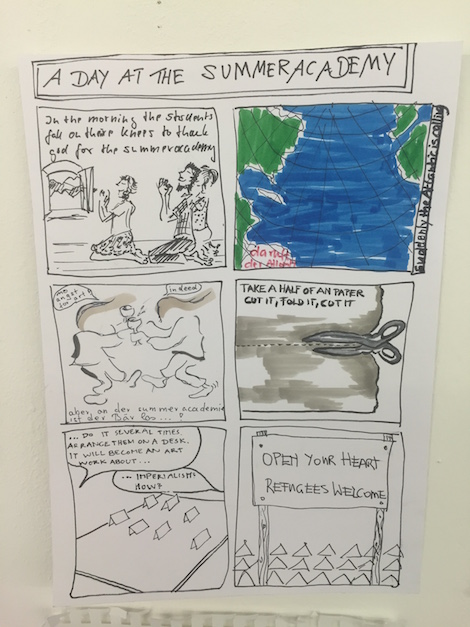

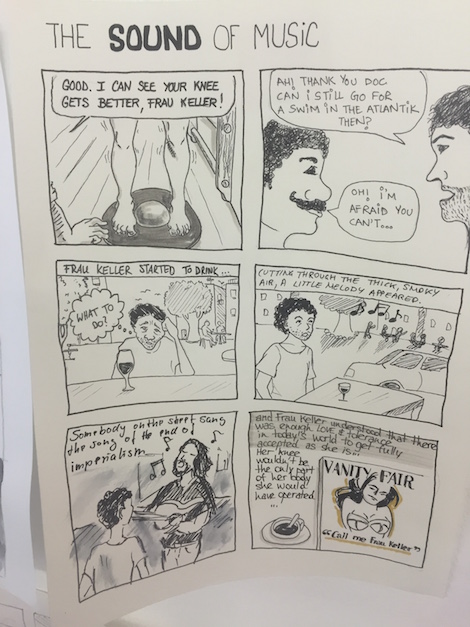

Exercise 1: I give you six words. Turn them into a comic story of six images. Each word has to make an appearance in at least one of the images.

Exercise 2: Draw the protagonist of a comic on a card. Write the title of comic story on another card. Exchange your cards with the others. Create a comic story from your two new cards.

I have been fascinated with graphic reportages for a long time. They are an often provocative mix between journalistic research and the aesthetics of comic books. As you can imagine, the styles reach from data visualizations to graphic novels based on real events. Nicolas’ last comic books documented his life in Kabul in Afghanistan. We leave his class to not disturb the others.

Let’s talk about graphic reportages. There seems to an interesting tension between the journalistic and artistic sides to it. How do you deal with claims for objectivity that journalism poses to your drawing?

It is impossible to make an objective drawing. Even an objective photo is impossible. Because when you draw, what you see is processed through your brain and then processed through your hands. Your hands also know things that you are not aware of. There are all those filters of reality that a drawing goes through. That is why comic books are so interesting. You can recognize the process that the writer or illustrator goes through when catching something. It’s really like a stage. You have to draw the expressions of your protagonists. You have to dress them. You have to give them a car and so on.

But you surely adapt your style to the story that you are telling.

It is always difficult at first to find a style that fits the story. Depending on what you want to tell, the style obviously changes. Tintin’s style has been designed to tell adventure stories for example. As a kid I got to know the world through Tintin. The first time I travelled to Tibet and the first time I travelled to the moon was with Tin Tin. Afterwards when I started to travel to different countries for reportages, I always had to think of Tintin.

Is this style and the humour connected to it a way to cope yourself with the serious reality behind your stories?

Two of my comic books were chronicles of my life in Kabul. When you live in Afghanistan you don’t think about violence and war all the time. You have an everyday life. So, you don’t usually pick the hard topics at first. In Afghanistan the people have a lot of humour. They laugh a lot about their tragedies. It is a way of surviving. So, I was paying tribute to the Afghan humour by doing something funny. Most of the stories that we know from Afghanistan are sad and depressing. So I said, lets make a comic to ease a bit the pain. Comics are good for the soul.

How does your teaching relate to your own work? How do you start with a new work?

I don’t do what I teach my students. (smile) I don’t go from idea to storyboard to drawing. When I have a general idea, I create some key sequences. Mostly, this is the first and the last sequence and some sequences that inspire me to continue working. And then the rest grows organically. Even when I am almost finished I move sequences and materials around. So, I am constantly re-writing the story even when I know how it ends. This works fine as long as you work alone and do everything yourself. When you collaborate with a writer or an illustrator this is a much more linear process.

Why is this important to you to create these visual reference points?

If you have the end of your book in mind, it is easier to write everything else. You never get lost, because you have a target, even if you take detours. For the first sequence you have to do something intriguing, something punchy. You have to grab the reader and say: come with me! We are going on an adventure! It’s like in a Shakespeare play. They always start with a storm or a sword fight. Because back then in theatre people were shouting and not paying attention. When you have a storm everybody is like: ok, now it starts.