| « 24 / 30 Black Boxes | 22 / 30 Writing takes time, writing takes space » |

23 / 30 Basic Research

“Basic research is what I’m doing when I don’t know what I am doing.” (Wernher von Braun)

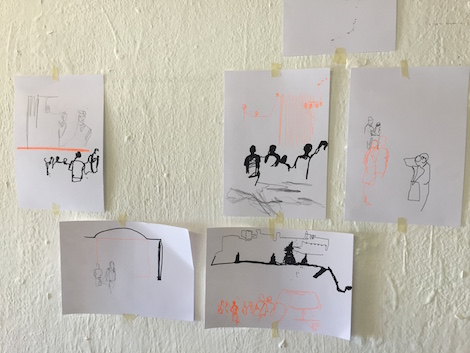

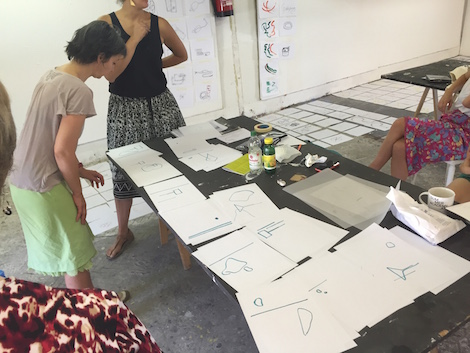

Three lines, a hundred times. This was the first instruction that Adriana Czernin gave the students in her drawing class. They had two days to create 100 drawings, each consisting only of three lines. “It is a concentration exercise, endurance exercise and an exercise to sensitise for the basic questions of what an image is.” I am impressed by the scientific rigor that the students develop in this exercise. Some students create subseries of ten or twenty drawings that focus on one idea.

What is a line?

Where does it start?

Where does it stop?

Is a line a movement?

Is it a space?

Is it abstract?

Is it figurative?

What is involuntary abstraction?

How does space come into existence?

All these questions come up in the discussion of the drawings. They remind of basic research. They are highly theoretical. A single drawing is barely important for itself in this exercise. Often an idea only becomes graspable when looking at a series. You see how concerns and questions appear and disappear when looking at all 100 drawings of a single student. In our conversation Adriana Czernin tells me about how to develop a dialogue with one’s work and why art needs particular modes of experimentation.

Tell me about your course. What are you doing and how did you start?

My course is about relationship between form and content. The relationship between form and content can be really dynamic during the process of creating something. You can start with a vague idea and after some time you look what actually happened. Sometimes it turns out that the result is not the idea that you initially had, but it might lead you somewhere else. Then you ask where does it lead me? Do I want to go this way? Do I want to work out more what is already there or do I go back where I started and look for another form for the idea that had? Or you do it the opposite way: you start with a form and that might lead you to an idea or content. This is a process that appears in almost all practices: a kind of a reflection that you have to develop as an artist. In our conversations, I really try to get students to start a dialog with their own works. They should learn their how works speak to them, as much as they speak to their works.

How does this work? How can you support such dialogue between artists and their works?

The students tell me about their ideas through some first drawings. Then I ask them to articulate and formulate in words what their intention is. Where do they think it will go from here? When I realize that what they are saying about the works does not match with what I see, we talk about it. I want them to understand that their work can look very differently to somebody who is not part of the process. I don’t say that my perspective is the right one, but I tell them that another interpretation than their own is possible. For me those attempts to articulate, to speak and to look are really important.

When observing your class, I found that experimentation plays an important role. Is that also true for your own practice? Do you also develop a series of drafts to arrive at the final drawing?

I often approach my drawings very slowly. I have to encircle an idea and go through an entire field of ideas to see what is actually possible. Most of the time these processes take a long time. I know that there is something, but I beat about the bush and I don’t arrive at the point where the different elements work together and lead to a concentration that is necessary for a work. Then at a certain moment, I find the right form. But I don’t stop. Through this form I then can look back at the entire field and I see what is possible. Sometimes this already leads to the next work.

You say that this process takes a long time, is that particular for the medium drawing?

It is specific for drawing that you don’t work that long on one piece. This is a great advantage of drawing: you are able to keep a phase and then rapidly go to the next one. After some time you have a collection of these different phases that you can then examine. You can realize that there is something interesting happening at the beginning of the series that later is lost, but then something else appears in the middle of the series that is absent at the beginning. In a next step I can then bring together these observations and work with them.

What do you do when you feel that a student is lost?

In such a case I really try to encourage students by looking at what they have done before. And I ask them: what are you mostly attracted to at the moment. When then say, I really want this, but somehow it does not work, then I try to find promising aspects in their work and point them to them. Maybe they have to go a little bit more consequently in one direction.

So you say, when you are lost, it is important to look back. It is important to ask, ok how did I get here?

Exactly, often the solution comes out of one’s own work. Stepping back often helps, because you can see with more objective eyes what is happening here. Every work changes according to the position you take towards it, at least you can change the focus of it. It also helps to see different works together that seem unrelated at first. Comparing these apparently unrelated parts can also help.

The most important thing is the process: that we talk, that we discuss, that we make, that we try out different techniques.